Books about shipping, to my view, veer towards two sides of the fairway - insider accounts that are punctiliously accurate but may fail to connect with radar of wider audiences, and, alternatively, views of outsiders, often a mainstream “journalist” looking in, more likely addressing broader societal currents and concerns.

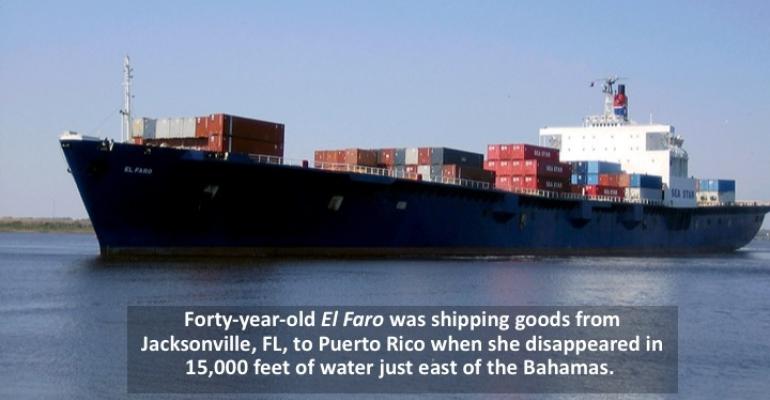

“Into the Raging Sea”, a newly released book about the sinking of “that ship”, by Rachel Slade, a Boston-based writer, successfully, and very powerfully, navigates the difficult channel between insiders and outsiders. Her writing style will appeal to readers of nautical thrillers interspersing a fast-paced narrative of what was actually happening aboard the vessel as it collided with 120 mph eyewall of Hurricane Jaoquin lurching through the Bahamas, with a rigorously researched backdrop covering commercial and regulatory issues.

Read More: El Faro believed to have sunk, one body found

Read More: El Faro believed to have sunk, one body found

The secret sauce, if I had to point to one ingredient is the human side. Through interviews with families of the deceased crewmembers, and an insightful read of the transcript of what was actually happening onboard, taken from a voice recorder on the vessel’s bridge, Slade is able to peer into the minds of those who perished.

Accident investigators, such as those at the US National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) will talk about “chains of errors”, in aftermath of transportation calamities with loss of life. Like other terrible tragedies, including highly publicized airplane crashes, there is almost never one single cause for the disaster. In the case of El Faro, Slade points a finger at human factors that we’ll never know precisely what was on the mind of the vessel’s Master as he seemingly pointed the vessel directly into harm’s way?

Unlike simplistic accounts in the popular press, she does not present Captain Davidson as a tyrant determined to meet a tight schedule, at whatever the cost. Rather, she presents him as an aloof personality trying to get a difficult job done in the wake of a corporate culture that put everyone on edge. Yes, his subordinates were offering alternative course headings, but he’d been through bad storms before.

Read More: Footage of sunken El Faro released

In retrospect, weather information he was receiving came with substantial, and deadly - we can infer later - time delays. And actionable information about flooding down below on the vessel, which brought about a list, which, in turn, brought about a failure in the turbines’ lubrication system prior to the propulsion shutting down, was non-existent. If anything, the Captain’s humanity is revealed in the final minutes on the vessel’s bridge, as he tries to coax a petrified seaman down towards the lifeboats.

The culture of the vessel’s owner, privately held TOTE Maritime, and the rusty state of the US deepsea merchant marine generally, probably receive the biggest thrashing as Slade seeks to illuminate the underlying failures in the chain.

Read More: Former El Faro crew members say ship suffered structural problems

TOTE, like one of Captain Davidson’s previous employers Crowley, operated in the hyper-competitive Puerto Rico trades subject to the Jones Act, which made replacement of older vessels, like 1975 built steamships, prohibitively expensive. Not surprisingly in the wake of shrinking profit margins, TOTE had consolidated its shoreside functions; the author places considerable attention on the absence of a coherent system for evaluating and acting upon performance of ship’s officers. Indeed, the company’s entire chain of command and its safety systems, or seeming lack thereof, is also called into question.

As the maritime industry, its regulators and its equipment providers now consider a myriad of recommendations from the NTSB, which held hearings on the sinking and published its report in late 2017, what changes might occur? And how do these align with failings identified in Slade’s book? One obvious failed link in the El Faro chain concerns lifeboats; the NTSB has recommended that the US Coast Guard mandate the use of closed, and ideally freefall, lifeboats, rather than open boats.

There are a number of recommendations concerning alarms; common sense would dictate the installation of audible alarms warning of high water levels at points of possible seawater ingress and around vessels’ holds and bilge areas, for example.

And then there is the weather; the NTSB has recommended experimentation with weather observations, from automated sensors aboard vessels, being tagged on to AIS transmissions, which would provide near real time feedback and adjustment loops that could be made available to providers of forecasts and weather routing.

Resource: Summary of NTSB Report into loss of El Faro

https://www.ntsb.gov/news/events/Documents/2017-DCA16MM001-BMG-Abstract.pdf

Into the Raging Sea:

By Rachel Slade

Copyright 2018 Ecco, an imprint of Harper Collins

Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved. Seatrade, a trading name of Informa Markets (UK) Limited.

Add Seatrade Maritime News to your Google News feed.  |