Ships themselves might be slowing down on passage, ostensibly to save the planet, but from the shippers who use them, to the management hastening them through ports, all are united to maintain their productivity, despite their more pedestrian sea passages.

Those aboard are urged to get their ships alongside faster and depart sooner, pilots in some ports being rated on their progress. Stevedoring firms are being told that carriers will take their business elsewhere if the dockers dally too much. Where once there was a degree of prudence, impatience and urgency are being almost bred into behaviour, on both ship and shore. The respectable phrase of “utmost despatch” has been relegated by a fierce injunction to be always in a tearing hurry.

How many expensive accidents can be attributed to this desperate urgency? If the master of the Ever Given thought that his management would tolerate a weather delay waiting for the cross winds in the Suez Canal to abate, might he have postponed his transit? There was that collision case that went all the way to the Supreme Court in the UK, with learned and very expensive counsel arguing about Rule of the Road – I wondered whether the issue of impatience was actually more relevant. Surely, prudence might have suggested that an inbound ship might have kept well clear of a port entrance while another vessel was leaving?

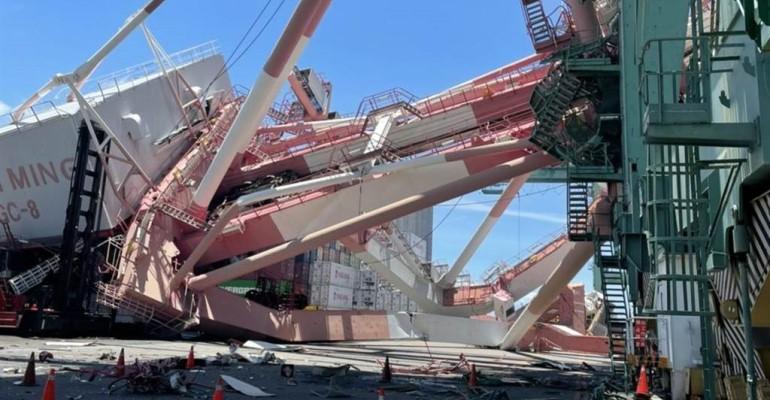

Scarcely a week goes by these days without viewing a video showing an inbound ship spectacularly wrecking a multi-million dollar ship loading gantry, in a cascade of crashing girders and flailing booms. You might argue that speed is essential to maintain steerage way, or the tugs were slow off the mark, but I just wonder whether less haste might have kept all that steelwork intact. And you might also find it relevant to make a connection with the urgency to get ships off to sea, the time available for lashing, and all those containers that ended up wrecked or in the sea

There are some highly relevant suggestions made recently by Gard P&I Club to those both afloat and ashore on car carrier berths, following expensive and spectacular incidents where these huge multi-decked ro-ros have ended up on their beam ends.

Heaven knows the advice offered is simple and basic and if a master or mate in a less frenetic era had been told not to leave the berth before the stability had been calculated, they would have been insulted at being told the blooming obvious. But the clues are contained in Gard’s preliminary remarks, pointing out that car carriers today operate against tight schedules and quick port rotations, with the cargo planning being done ashore. Is there any need to say any more? Will the world end if they slow down a bit?

But what is also absent in the practices that lead to these nasty incidents is any respect or latitude being shown to those aboard the ships, who have to take them \away to sea. It’s that “tearing hurry” – the cargo has finished - raise the ramp, shut the door and let go fore and aft.

Gard notes that cargo planning can be something of a moveable feast – nothing wrong with that, if the ship is informed in a timely manner about alterations to the cargo plan, so that stability calculations can be adjusted. It is pointed out that the ship needs more than just estimates of weights – accurate weights are essential along with a proper stowage plan, not something that follows the ship in an email as she leaves port.

And the P&I club urges the master not to leave the berth until stability calculations are complete. If they are not, the departure should be delayed, although in “real life” you might imagine the screams and threats that may follow such a thoroughly sensible and seamanlike action. But a bit more respect for the ship and some thought to the possible consequences of instability would not go amiss. Slowing down does indeed save lives.

Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved. Seatrade, a trading name of Informa Markets (UK) Limited.

Add Seatrade Maritime News to your Google News feed.  |